Apr 11, 2023

I’ve been working with the principles and practices of Dialogue Education for more than a decade. I’ve come to feel as if too little has been said about the content of our courses, workshops, and classes — how we find content, how we shape it, how we select it, and how we weave it into our learning-centered designs. I’ve found that content can be a lot trickier to work with than we admit and paying too little attention to the quirks of content can get us into trouble as designers. I hope to shine a brighter spotlight on what we affectionately call “The What” in the 8 Steps of Design and share a few insights I’ve discovered over the years.

Well-Crafted Content Can Anchor Action in a Learning-Centered Design

For some of us, working with content may be the least exciting part of the learning design process. Given the way we sequence the steps of design in Dialogue Education, our concern with content can feel like a precursor to action — something we need to get through before we can focus on the “how” of our courses. After all, content just sits there on the page or in the PowerPoint deck, doing very little until we bring it to life with vibrant tasking language that invites students to parse a new idea, practice a new skill, or debate a new perspective. Others may fear that by concerning ourselves too much with content, we’ll end up de-centering learning — in the form of action — in our designs. But well-researched, precise, and appropriately sequenced content creates an anchor for all the action in a learning-centered design. It keeps the creative energy that comes from doing-in-dialogue from scattering off in a million different directions.

Sometimes we need to help our clients and subject matter experts discover, for the first time, what it is they think they already know and have on hand to share. Time and again, I’ve seen a lack of appreciation for the effort that goes into really nailing the content of a course. Designers, clients, and subject matter experts will take for granted that content already exists in a format that lends itself to being used in a learning design, and they fail to plan for the work that will inevitably go into finding, organizing, parsing, re-sizing, or simply creating content appropriate for a specific course. “We’ve got all that in the PowerPoints on the computer,” I’ve heard one client say, shooing away the need to work with a researcher or a writer to cull through hundreds of repetitive, incomplete, and sometimes indecipherable slide decks to find a few gold nuggets in a river of silt. As designers, we need to be ready to take a pile of disorganized information and weave it into the valuable knowledge at the heart of every bit of content in our courses.

Skills, Concepts, & Perspectives: Content as a Collection of Nouns

Instructional designers working in the tradition of Dialogue Education intentionally treat the content of their courses like a collection of inert objects — a collection of nouns — that their students will work with in some practical, meaningful, and intentionally sequential way. Content comes to life when students are tasked to do actively and demonstrably do something with it — debate it, discuss it, re-define it, dissect it, diagram it, model it, or even simply read it (to name just a few examples from a long list of possible verbs). Deciding how to task students with bringing content to life is an important step that comes later in the design process. First, designers must strive to make each piece of content a complete and independent idea, perspective, or action—like “tying shoelaces” or “the U.S. Bill of Rights” or “debates on lowering the legal age to vote.”

Sometimes “content” gets confused with “media” — probably because the words are used interchangeably in broadcasting and entertainment. Media (or, even, “materials”) are the things that convey the content: the chapters, books, articles, videos, podcasts, lectures, and, very often, PowerPoint slide decks — all that communicative stuff that encodes and serves up a skill, concept, or perspective. Instructional designers will sometimes confuse content with media because they focus on the specific medium where they first discovered a new skill or concept—that favorite book or memorable tutorial that finally helped them get their minds around a complex idea or their hands around a tricky skill. But many different media can get across the same bit of content, and a big part of any designer’s job involves finding the right media to fit the needs of a particular course and its students. When no pre-existing media exists, the designer must create it from scratch. In my own design work, I’ve rarely had the luxury of finding an off-the-rack trove of well-developed content on any topic around which I can immediately design a workshop. A little bit of tailoring is always necessary to make it all fit.

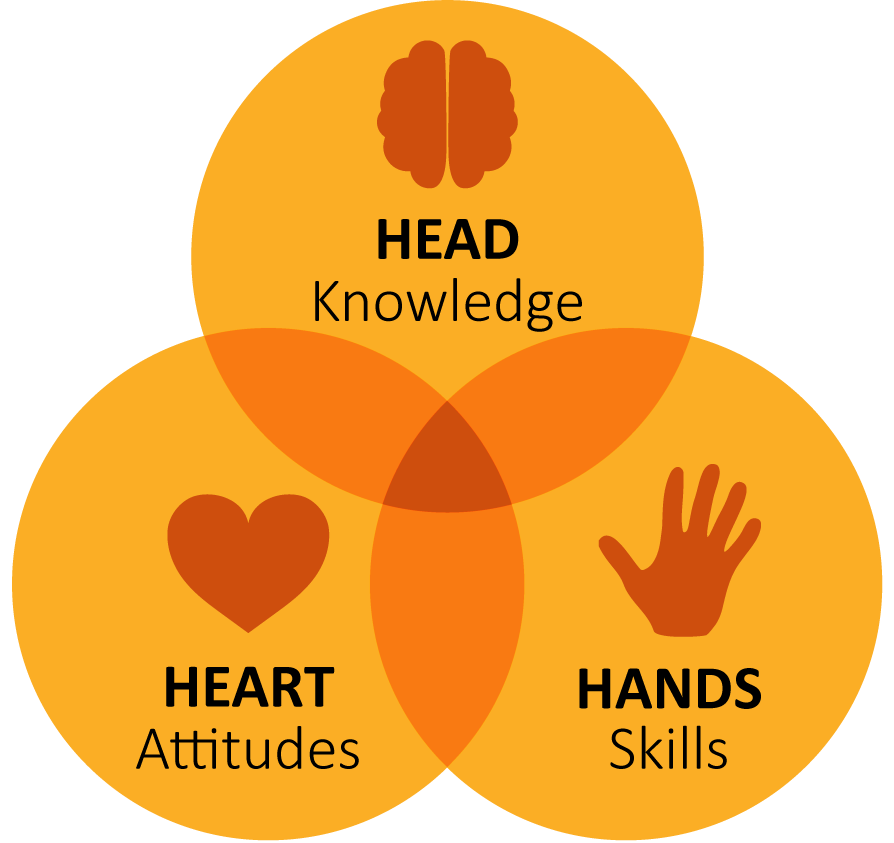

Dialogue Education teaches that content comes in three basic categories: 1) concepts, or ideas that mostly live “in the mind” or “on the page” and include facts, dates, stories, theories, or statements on a particular topic; 2) skills, or step-wise processes and practices that add up to an active “know-how” involved in performing an action of some kind; and 3) perspectives, or feelings, emotions, opinions, attitudes, and intuitions that often shape our conceptual thinking and power our skillful actions. Don’t get tangled up in knots trying to figure out whether some chunk of content is a skill or a concept or perspective. Content can often live in all three simultaneously, depending on what’s being emphasized. The model seen here used with permission by Global Learning Partners.

For example, “tying shoelaces” is, on the face of it, a skillful piece of content. But it might also show up as a perspective if it makes a case for one approach to shoelace tying over another. Or it might appear as a concept if it emphasizes the history of shoelaces (in case you were wondering, shoelaces didn’t become a popular way of making shoes fit snugly around feet until the late 19th Century). Think of these three categories as generative ways of thinking about content rather than prescriptive. We use them to ask ourselves, “What are all the skills that need to show up in this course? What are all the concepts we should explore? What perspectives need to be included?” Instead of wasting energy trying to shoehorn content into one category or another, we ask ourselves, “How might this show up as a skill and a concept and a perspective?” Taking this generative view will almost always result in new and surprising insights into how a piece of content might best appear in a course.

“Chunking” Content With “Miller’s Law”

Dialogue Education is, itself, a collection of skills, concepts, and perspectives—a body of knowledge—made available to us in Jane Vella’s research and writing. In her books, Jane takes more than a century of incredibly complex thinking and practice in adult education and shapes it into pieces of clear, precise, crisp, and accessible content. Consider the 8 Steps of Design, the 4A Learning Sequence, or the Three Domains of Learning—some of them Jane’s innovations, others directly cited from other sources. They’re all tidy “chunks” of content, ready for Jane’s readers to more quickly grasp and, perhaps more importantly, ready for designers to work into their workshops and courses on Dialogue Education.

“Chunking” content involves taking big, unwieldy ideas or long multi-step actions and breaking them down into more accessible pieces. Imagine deciding that “algebra” is an essential concept for a course you are designing. Now, let’s be real. An entire year of high school is devoted to teaching just the basics of algebra—and even that isn’t enough to cover everything there is to know about the subject! Admitting this, an instructional designer begins to break a giant topic into smaller chunks, and then break those chunks into even smaller chunks, and on and on until they arrive at an appropriately sized idea or a succinctly sequenced skill or a tightly defined perspective. There are no stopping rules for when to quit breaking content down into smaller and smaller pieces. Designers need to use their best judgement, including their knowledge of the purpose of a course and the objectives it aims to achieve, to appropriately size each skill, concept, or perspective.

Take the concept of “household budgeting.’ Imagine the hundreds—maybe even thousands—of different concepts, practices, and perspectives that have to do with “household budgeting.” It would be impossible to explore every facet of household budgeting in a short workshop, or even a series of short workshops. There’s just so much to explore! A more focused concept might be “reasons for making a household budget;” a more manageable skill might be “steps for making a simple household budget.” But even these chunks of content are likely too big to work with in one sitting. This is where a little thinking tool called “Miller’s Law,” or the “Law of Seven—Plus or Minus Two” can be a handy tool for right-sizing content for any course.

In an influential research article published in the mid-1950’s, the psychologist George A. Miller proposed that human short-term memory has “severe limitations on the amount of information that we are able to receive, process, and remember.” According to Miller, we can only work with seven bits of information (give or take two) at any given time. Phone numbers in the United States are designed to work with Miller’s Law, breaking a string of ten hard-to-remember digits into three easier-to-memorize chunks (with dashes between them). As children, we learn our home phone numbers in a sing-song way, reciting the first chunk, pausing, reciting the second chunk, pausing, and then finishing with the final four digits. Wisdom traditions from around the world knew about Miller’s Law long before George put pen to paper—consider the Four Noble Truths from Buddhism or the Seven Deadly Sins from Christianity. These lists helped adherents remember very complex ideas in societies where things didn’t get written down very often. Miller’s Law even helps explain the modern proliferation of “listicles” online—articles that structure content as “ten things you need to know…” or “seven steps you need to take…”.

Adhering to Miller’s Law, any individual chunk of content should be comprised of no more than five to nine key ideas, actions, or perspectives. Any more would make it too complex and multi-faceted for students to effectively work with. Of course, not every chunk of content needs to get the list treatment. As the neuroscientist David Rock points out, the ideal number of items to try and store in a brain’s short-term memory is just one—which leads me to believe we can always go a little further in our efforts to make content more crisp, precise, and workable.

What tip can you offer for selecting relevant content for your learners?

Philip Silva is a Certified Dialogue Education Teacher living and working in the New York City region. He has designed adult learning and collaborative group processes for the Environmental Leadership Program, Design Trust for Public Space, Brooklyn Botanic Garden, Central Park Conservancy, National Recreation and Park Association, and many others.