Oct 22, 2019

Some years ago, I led a workshop that was based on an outline I had developed and used in previous settings. At earlier events, the activities and script had been well-received, including a humorous anecdote about shoveling snow in my hometown of Chicago that always generated chuckles from the audience. On this particular occasion, I related the story only to be greeted by blank stares from the attendees. The problem? This latest iteration was held in Palmer, Alaska. When you average over six feet of snow each year in a vast rural area, shoveling a sidewalk for pedestrians is not the first thing on your mind. Awkwardly, I moved on, promising myself to review the materials a bit more critically before the next event.

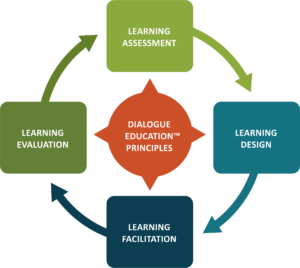

Knowing your audience is the foundation of any good education. More than merely saving an educator from embarrassment, the Learning Needs Assessment is a key cog in the Principles-to-Practices Framework of Dialogue Education:

This front-end assessment can make the difference between learning that flourishes and learning that fails. Helping learners see themselves in the material will enable them to find the connections between the lessons being taught and their own daily lives. This, in turn, will foster deeper engagement with and longer retention of the information.

Most facilitators understand this, even if they aren’t always sure how to do it. This is especially tricky when the educational event is based on a curriculum or resource that has been developed by someone else. In my work with a faith-based organization, I direct the development of curricula and guides that will be facilitated by other people, such as Vacation Bible School programs for churches, adult study programs and book series. The design of these happens one step removed from the facilitation, and we trust that the facilitators will be equipped through the guide and their own talents and experience to lead effective events.

Below are some tips for equipping educators for effective assessment of learners by building these elements into curricula and resources.

1. Do the Research

In recent years, user-centered design has gained more popularity in education and pedagogy. This is in contrast to design focused on a process (“I have to do a Power Point!”) or content-centered design (“I have to teach to the book!”) In user-centered design, the experience of the learner (the “user”) lays the groundwork for other design decisions.

When writing resources or curricula, we try to learn as much as we can about the learners from research. This can include anecdotal research from our own experience and more formal research about learners in particular settings. Because our audience is faith-based, this might include articles or books about faith-based education for certain audiences, changing demographics of church attendance, etc. It also includes a lot of conversations with facilitators about their communities before we start writing.

Most of this research makes its way into the resources we develop, sometimes just as a callout box on a printed page or via a hyperlink in an online guide. More formatively, this research sets the stage for how the resource is structured, so that facilitators understand that certain elements are structured based on research about their learners.

In each case, being explicit about the design is critical. By helping facilitators see how the resource has been designed, they’re encouraged to consider how both the design and the facilitation can best suit the learners’ needs.

2. Flexibility Markers

Our organization, the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America (ELCA), is a denomination of about 3.3 million members spread across the United States and Caribbean. Trying to develop a “one-size-fits-all” resource is nearly impossible, so we aim for resources that can be used in a variety of settings. When developing a leader’s guide for adult education on economic justice, we included five sessions, each lasting about 45-60 minutes. For many groups, hosting five one-hour sessions is outside what the learners may be familiar with (or able to handle.) So, in developing it, we made sure to build the sessions so that the learnings were not sequential. This way, a group could do one, two or five sessions and still have an effective learning experience.

Non-sequential sessions are examples of what I call a “flexibility marker” – a design element in a resource that equips a facilitator to adapt a resource in whole or in part to their audience and setting. Other examples of flexibility markers are alternative activities that address different ability levels. For example, in a curriculum for youth that included a lot of high-energy, high-movement activities, we also added activity suggestions that would meet the needs of participants with limited mobility, as well as suggestions for adapting activities based on ability.

Flexibility markers equip educators – who know the needs of their learners best – to make adjustments that meet these needs. One important thing to remember is that flexibility must be explicit. Too often, a learning resource is developed and written assuming strict adherence, so facilitators may not feel empowered to adapt. By making this flexibility explicit and using a variety of flexibility markers, facilitators will feel equipped to use their own knowledge of learners to adjust and adapt to meet diverse needs.

3. Asking the Right Questions

In addition to making adaptation easy, outlining explicitly the kinds of questions that can help ground facilitation is helpful. Suggesting that facilitators consider certain questions about learners as they plan is a great way to incorporate this. For example, a facilitator guide might include a list of “questions to ask as you get started,” such as:

In addition to making adaptation easy, outlining explicitly the kinds of questions that can help ground facilitation is helpful. Suggesting that facilitators consider certain questions about learners as they plan is a great way to incorporate this. For example, a facilitator guide might include a list of “questions to ask as you get started,” such as:

- What is the age range of your audience?

- Will the learners have prior knowledge of the topic?

- Are the learners high-energy and need to be physically active during the session?

For resources that involve sharing or preparing meals or snacks, we also encourage considering dietary restrictions, so facilitators are advised to ask about their learners’ preferences or needs. Because our resources often involve topics of hunger and poverty, encouraging facilitators to plan facilitation that is sensitive to the economic situation or background of learners is essential.

No matter the form it takes, a short section that helps facilitators ask the right questions about their group will go a long way in helping them make the resource their own through adaptive, user-centered facilitation. This can help them conduct a useful Learning Needs Assessment in an informal way.

Designing curricula, resources, guides and other materials for facilitators is a great opportunity to equip them for the essential tasks of effective education, including the assessment of learners. Building the materials with this in mind can help equip and encourage facilitators to see how to adapt the materials – and how to gather the information they need to guide that adaptation. This can happen in hidden ways, like research-based, user-centered design, and more visible ways, such as a short list of questions to consider as they plan their event. Using both methods can improve the likelihood that groups will use the materials – and the likelihood that the learners will come away with long-lasting, meaningful education because of it.

How have you included learner assessment in developing materials for other facilitators?

*****

Ryan P. Cumming, Ph.D., is the Program Director of Hunger Education for ELCA World Hunger. In addition to this role, Ryan is a senior lecturer with Loyola University Chicago’s School of Continuing and Professional Studies and an instructor with Central Michigan University’s Global Campus.